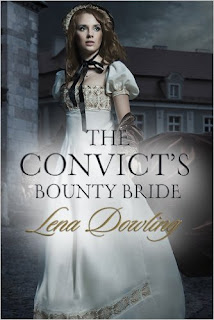

2 stars

You could be forgiven for thinking a book entitled The Convict's Bounty Bride would be set in the colony, but you'd be wrong. If you read between the lines of the synopsis, you can see it's set in London, but somehow I still expected that it would end up back in Australia at some point. It never did, but my annoyance at that was quickly overwhelmed by my annoyance at just about everything else.

Quick plot run-down before I get all rant-y: James Hunter has served his seven-year sentence in the colony of New South Wales, and returned to London to claim his due from the family for whom he took the fall. Lady Thea Willers' father was counting on James dying during his sentence, but now James is back and demanding Thea's hand in marriage. Except Thea doesn't want to marry, instead having entirely unrealistic expectations about what she is going to do with her life (more on that later).

The combination of the writing style and novella-length made the story feel very abrupt. There was little attempt made to orientate the reader or set up the plot and characters, and the results are jarring. The whole thing gallops along, and - to continue the terrible equine metaphor - the reader can barely keep her seat for being whacked by passing plot twists. Literally every development in this book came out of nowhere and made its appearance too soon.

You could be forgiven for thinking a book entitled The Convict's Bounty Bride would be set in the colony, but you'd be wrong. If you read between the lines of the synopsis, you can see it's set in London, but somehow I still expected that it would end up back in Australia at some point. It never did, but my annoyance at that was quickly overwhelmed by my annoyance at just about everything else.

Quick plot run-down before I get all rant-y: James Hunter has served his seven-year sentence in the colony of New South Wales, and returned to London to claim his due from the family for whom he took the fall. Lady Thea Willers' father was counting on James dying during his sentence, but now James is back and demanding Thea's hand in marriage. Except Thea doesn't want to marry, instead having entirely unrealistic expectations about what she is going to do with her life (more on that later).

The combination of the writing style and novella-length made the story feel very abrupt. There was little attempt made to orientate the reader or set up the plot and characters, and the results are jarring. The whole thing gallops along, and - to continue the terrible equine metaphor - the reader can barely keep her seat for being whacked by passing plot twists. Literally every development in this book came out of nowhere and made its appearance too soon.

Because the characters are very one-dimensional, the reader is unable to anticipate their actions, which was probably a blessing in disguise. I probably would have given up altogether if I'd known the heroine would be so horrible. She was, by turns, immature, cruel and criminally stupid. There's a scene where, determined to ruin herself so as not to be forced into marriage, she basically assaults the stable boy in full view of the stable master. And then she's so surprised her father is going to whip the poor boy - who might also lose his position - that she faints.

The other reason I was completely baffled by the characters' actions is that they just don't act in the way real people do. When there is a Big Tragedy, the affected characters all have very weird and unrealistic reactions. James is the only one who actually shows any sense, but even this doesn't last long, as he proceeds to take Thea's virginity at a totally inappropriate time.

As much as I disliked the Thea, I also didn't appreciate the way James viewed her as payment for services rendered. He never really gives up seeing Thea as an object; when he realises he cares for her, the reasons that are given are basically her body and her suitability as a colonial wife.

But the biggest single thing was the lack of regard for the realities of the Regency Era in which the book was set. I mean, I'm no Georgian scholar, but I'm pretty sure random ex-convicts can't get vouchers to Almack's. And then there's Thea. The book opens with her asking her father if she can have a position on the board of their bank, because she wants to have a career. Dowling justifies this by referencing the fact that the famous Regency character Lady Jersey was the primary shareholder in her grandfather's bank, but I'd argue that it's one thing for a married Countess and social arbiter to be involved in banking, and another for the young, unmarried daughter of an Earl.

The idea of Thea having a 'career' is odd. It is surely anachronistic for a young woman to aspire to such a thing (especially in something like banking, instead of say, writing), and I'm also pretty sure the concept of a 'career' was not commonly used in the same sense as we use it today. One had a profession, or a vocation. Where 'career' was used, it was because one had chosen a calling with steps of advancement, such as the military, rather than just some girl deciding to dabble in banking.

Supposedly, Thea's desire to be a career girl comes from Mary Wollstonecraft, whom her father included in her education. That, in of itself, is a stretch, but I was willing to let it slide. But Thea's refusal to marry was based on a erroneous belief that Wollstonecraft never married, and I couldn't believe that she would not have known this. Even though Wollstonecraft had been dead for roughly 20 years, she still lived on in the Ton's imagination because of the exploits of her daughter Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein), whose affair with the married Percy Bysshe Shelley was grist for the gossip mill for years. Basically, everyone thought that Mary Godwin was no better than she ought to be, given her scandalous and unnatural mother.

But, if the idea of a Wollstonecraft-loving heroine appeals, I'd recommend The Likelihood of Lucy by Jenny Holiday, where the heroine won't give you homicidal impulses.

The idea of Thea having a 'career' is odd. It is surely anachronistic for a young woman to aspire to such a thing (especially in something like banking, instead of say, writing), and I'm also pretty sure the concept of a 'career' was not commonly used in the same sense as we use it today. One had a profession, or a vocation. Where 'career' was used, it was because one had chosen a calling with steps of advancement, such as the military, rather than just some girl deciding to dabble in banking.

Supposedly, Thea's desire to be a career girl comes from Mary Wollstonecraft, whom her father included in her education. That, in of itself, is a stretch, but I was willing to let it slide. But Thea's refusal to marry was based on a erroneous belief that Wollstonecraft never married, and I couldn't believe that she would not have known this. Even though Wollstonecraft had been dead for roughly 20 years, she still lived on in the Ton's imagination because of the exploits of her daughter Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein), whose affair with the married Percy Bysshe Shelley was grist for the gossip mill for years. Basically, everyone thought that Mary Godwin was no better than she ought to be, given her scandalous and unnatural mother.

But, if the idea of a Wollstonecraft-loving heroine appeals, I'd recommend The Likelihood of Lucy by Jenny Holiday, where the heroine won't give you homicidal impulses.

No comments:

Post a Comment